Our research is about how mothers and their babies engage with each other during the process of learning

Mothers are their baby's first, natural teachers. Even before her infant learns verbal language, a mother will use non-verbal cues like gaze and touch to engage her baby's attention, and to teach her about the world. Although joint (shared) attention is important for helping babies to learn from important social partners, very little is currently known about how our brains behave and engage during these moments of shared attention.

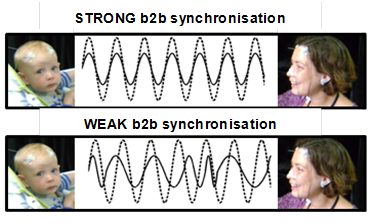

We are interested in whether mothers' and babies' patterns of brain activity become more synchronised when both are paying close attention to each other, and whether this brain-to-brain synchronisation might help to support babies' early steps in learning.

To investigate this question, we are using wireless dual-electroencephalography (EEG) to simultaneously measure the neural oscillatory activity of mothers and infants whilst mothers engage their babies in a variety of learning tasks.

Synchrony through Gaze

Our latest work has shown that when adults and infants make eye-contact, their brainwaves also become more synchronised too! This study was recently published in Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences (PNAS):

http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2017/11/27/1702493114

In the first of two experiments, infants watched a video of an adult as she sang nursery rhymes. First, the adult – whose brainwave patterns had already been recorded – was looking directly at the infant. Then, she turned her head to avert her gaze, while still singing nursery rhymes. Finally, she turned her head away, but her eyes looked directly back at the infant.

As anticipated, we found that infants’ brainwaves were more synchronised to the adults’ when the adult’s gaze met the infant’s, as compared to when her gaze was averted. In the second experiment, a real adult replaced the video. She only looked either directly at the infant or averted her gaze while singing nursery rhymes. This time, however, her brainwaves could be monitored live to see whether her brainwave patterns were being influenced by the infant’s as well as the other way round.

This time, both infants and adults became more synchronised to each other’s brain activity when mutual eye contact was established. This occurred even though the adult could see the infant at all times, and infants were equally interested in looking at the adult even when she looked away. We think that this shows that brainwave synchronisation isn’t just due to seeing a face or finding something interesting, but about sharing an intention to communicate.

To measure infants’ intention to communicate, we also measured how many ‘vocalisations’ infants made to the experimenter. As predicted, infants made a greater effort to communicate, making more ‘vocalisations’, when the adult made direct eye contact – and individual infants who made longer vocalisations also had higher brainwave synchrony with the adult.